From the cradle of centuries-old national traditions inherited from one generation to the other, uniquely emerges the man living in the Lori Region of Armenia (hereafter “Loreci”), with his ancient beliefs, profundity, customs, prejudices, creative and constructive rhetoric of noble aspirations, his unbreakable will to live freely and independently, and his great faith in a bright future.

The traditions purely unveil the peculiarity of national character and spirituality of the people. They are deeply immersed in the manners and customs, beliefs, the ideology and phenomena of people’s socio-economic, labor, political and cultural lifestyle.

Realizing and weighing the value of traditions, Lori has surrounded itself with opaque forests and castles as if trying to carefully conceal and cherish the national heritage entrusted to him from the depths of the ages in its deep valleys and gorges. The air is full of mystery here. Each corner reveals the story and presents the local culture, national traits, and values from its perspective.

The people of Lori are naïve: “naïve Loreci”. This is how we are described for our honesty, hospitality, kindness, generosity, and compassion.

Yes, they are naïve. Naïve because they live in their reality and believe the unbelievable trying to convince others as well.

Where else, if not in Debed Canyon, is it possible to see a man living a simple rural life, who, from time to time, cutting himself off from the concerns of everyday life, tries to extract the contribution he has been cherishing for years from his “wrinkles of wisdom” and instill the seeds of traditional values in the hearts of youngers, which will become a providence for the future generations.

Well, let’s look into some of these traditions to get a vivid understanding of Loreci’s wellspring of inspiration and value system.

Cry Djolie, cry!

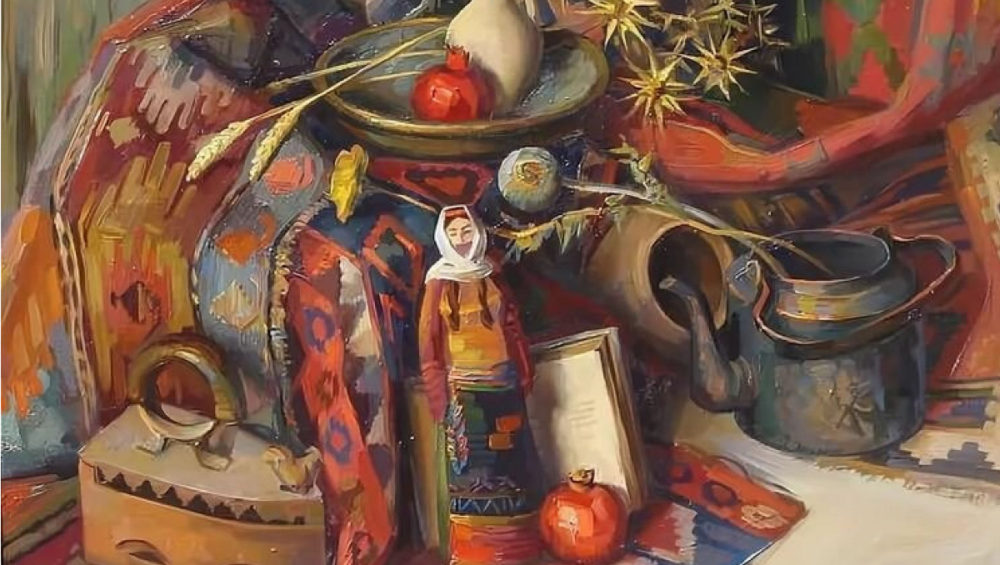

Have you ever seen a crying doll? “Crying Nuri” (the people of Lori called her “Djolie”) was considered to be a symbolic doll of Tsaghkazard (the ancient Armenian Flower Festival/Palm Saturday), who the villagers were asking for rain. This beautiful, bright, colorful, and amusing holiday was becoming more marvelous thanks to this doll.

In ancient times, the people of Lori had worked out their way of struggle against the lack of water. They had given a soul and breath to a doll ascribing their innocent beliefs to her. The people of Lori embodied their benignity and merciful nature in this doll. They were waiting with great expectation for Nuri-the sponsor of life-giving rain, to provide the thirsty fields and gardens with water: she should weep to water the soil with her tears and help the fields to revive. Djolie was bright, beautiful, and flowery. She had long hair and big eyes. Her shirt was lightly patterned and the belt was woven of seven rainbow-colored threads.

In various provinces of Armenia the ancient Nuri dolls were made of broomsticks or wood, always crowned with the wreath and completely decorated with flowers.

The celebration was to start early in the morning. Dancing with Nuri, the girls were going from house to house singing and giving blessings to the family members. People were spraying water on Nuri “to make her cry”. The aged woman of the house was providing the children with some food: eggs, bread, or cheese. If by chance, it rained, the children would rejoice and get delighted because Nuri had heard their prayers and favoured them with rain.

So, it becomes obvious that water has always been a significant source of hope, despair, joy, sorrow, dreams, and religious worship for Armenians. The above-mentioned role of water in the plant and the harvest of the country, the economy, and people’s lives, has left its indelible mark on the traditions of Debed Canyon.

No more butter for me?

Many will prove that Loreci people are really friendly, hospitable, and generous. They take advantage of every opportunity to organize a party trying to get rid of daily worries. We can safely assume this entails the way there is always a special delight and enthusiasm to welcome Barekendan (the Carnival). It was considered to be the warmest, happiest feast for the people of Lori, a holiday full of festivities and plentiful food – two weeks of dances, games, parties, plays, visits, and joy.

There was no restriction on the amount of food. Preference was given to the abundance of meat, dairy, and butter. To have plenteous butter, the people of Lori had developed a special tradition ingraining it in the ideology of Barekendan. Every year, on that day, the brides were asking the great-grandmother of the house (who they called nan / nani) to sit on a swing and make butter. As nani sat down, the brides were putting a stone on her lap, and instead of rocking it, they were twisting the rope and then releasing it. At that moment, the nani was dropping the stone from her lap, saying: “This piece of butter is for me.” One of the brides was immediately taking the stone and putting it again in the grandmother’s lap, so that after turning once more, she would throw the stone again and say: “This one – for my daughter-in-law,” and so on, for all the brides of the house in order to have an abundance of butter.

As you might notice, the dolls have always been one of the emblematic and mysterious values of Debed Canyon’s traditions. The mentality of people was most vividly embodied and engrained in the character and mission of these dolls. The symbolic birth and death of the dolls were accompanied by special rituals and magic. People have endowed them with supernatural power to prevent and protect them from danger or evil. With the help of dolls, they tried to ensure the abundance of crops and harvest, fertility, family, and personal success. In Lori the symbols of Barekendan were the dolls Utis Tat (Grandma)”, Pas Pap (Grandpa)” (or as the locals were calling – “Aklatiz”). Utis Tat was the symbol of Barekendan, Pas Pap was symbolizing the Great Lent. On the last day of the holiday, when parties and entertainment were in full swing, the women were performing ritual dances, and young boys were making the ritual doll – Utis Tat. It was a woman-shaped, torn, ragged doll that was solemnly rolled off a mountain to welcome Pas Pap. Utis Tat and Pas Pap were in a constant ritual struggle.

Their argument is expressed in the following passage of Lori’s folklore: “Grandma went with the ladle in her hand, Grandpa came with a crook on his shoulder”. According to the people of Lori, Pas Pap was hitting on the grandmother’s head with a large ladle of bean soup, kicking her out of the house for weakening the children’s souls by serving them porky and meaty foods. And at the end of the Lent, the happy and energetic grandmother was coming and slapping Pas Pap on the head with a greasy ladle of matsoun (yoghurt), was pulling out the thin, weakened grandpa.

As mentioned above, Utis Tat was the doll in torn, ragged women’s clothes, whereas “Aklatiz ” was personifying the doll in the form of a stubborn old man. He was appearing on the morning of Lent, bringing with him a whole series of rituals that were to ensure fertility and wealth.” Aklatiz” was made by the oldest woman in the house, secretly from everyone. The doll was an onion (potato, dough ball) with seven feathers on it. They represented the Fasting period of seven weeks. A feather was removed at the end of the week. The one-legged wooden doll, having a heavy mustache and beard, was put on the onion, dressed in men’s clothes, with stones hanging from the left and right forearms. He was to ensure that no one in the family broke the Fast all the while.

On the last day of Lent, after removing the last feather, the guys were taking “Aklatiz” to the pastures, mocking and hitting him with crooks who were throwing him into the water. The housewives used to keep the head of ”Aklatiz” – the onion or onion sprouts to use in meals.

Hurry up, the water is turning into gold

The inherent piety and naivety of the people of Lori were expressed in their convictions about New Year. They believed that on New Year’s Eve, all the flowing waters were turning gold for a split second, and if you managed to take a pitcher of water from a river or spring, it would immediately turn into gold as well. Or if you submerge something in the water at that stage, it would take on the appearance of the object you were dreaming of. It is no coincidence that pouring water from the house on New Year’s Eve was forbidden by local tradition.

In Lori, New Year was often associated with “Wood log” customs. The father of the house used to put a long log into the wood stove (usually placed in the main living room), the edge of which was mostly out of the house. In no way should the fire of the house cease down from New Year’s Eve until Christmas Eve. Then, on Christmas night, people were picking up the charcoals and burying them in the ground so that the New Year harvest would be plentiful and the fields would not be damaged by hail. The charcoal was even kept for the further usage-in case of hail, they were dispersing them to stop the thunder and pacify the sky.

For Loreci people, the main New Year preparations were centered on food. On December 30-31, the housewives were diligently cleaning the beans, peas, lentils, rice, and grains to decorate the festive table with various dishes. Bean and bean dishes were of special importance to the people of Lori. “The New Year will not come without beans,” they were surely declaring. However, the core of the December 31 holiday preparations and customs were a variety of pastries. Bread baking was a top priority in each house. “We should welcome the New Year only with fresh bread” It was the very time to bake the most important “Tari Hac” (Bread of the Year). It could be gata (made with flour, butter, and yoghurt, and stuffed with a mixture of butter and sugar), unleavened, egg-shaped, oval, triangle, cross, etc., just the way you prefer.

In addition to “Tari” bread, Loreci people were baking “magical cookies” of various shapes and sizes and “mysterious pastries” endowed with the power to predict. In order to make predictions, the people used to bake human-shaped and animal-shaped cookies according to the number of family members. The human-shaped pastries (with raisins on the eyes, mouth, and hands) were known as “Asil-Basil” in Lori. The swelling or shrinking of the pastries during the baking process was believed to positively or negatively impact the year, respectively. For example, if the belly of the pastry representing the woman swelled while being baked, a new baby would be born in the family. The people of Lori were also baking round pastries with holes in them, which they were gently calling “klka” or “ghula”. They were the symbol of “tonir” (an oven in the form of a deep round hole in the ground, the walls of which are lined with stone). According to tradition, on New Year’s Day, they were put on buffalo horns so that the barns would be filled with wheat that year.

Welcome to Debed Canyon – a place full of traditions, legends, amazing customs, rituals, mystery, but at the same time known for its simplicity, sincerity and generosity.

Some of the photos were taken from the Google